Back to News

Back to News

18 June 2021

In conversation with Professor John Coffey and Dr Anna Harrington of the Wilberforce Diaries Project

Politician and abolitionist, William Wilberforce kept diaries from 1799 to 1833 and the Wilberforce Diaries Project at the University of Leicester is opening up rarely seen manuscripts and making these accessible through transcription and new interpretation, remodelling our understanding of Wilberforce and British abolitionism.

In this lockdown conversation, Articles for Change Project Officer, Sarah Coleman, caught up with Professor John Coffey and Dr Anna Harrington from the Wilberforce Diaries Project to find out more and piece together references to Wisbech's Thomas Clarkson.

Sarah: How have you found working throughout lockdown?

John Coffey: We’re fortunate in that we have photographs of all the manuscript diaries and journals. So it’s been relatively easy to keep working on the project from home. But we have missed the archives. There’s nothing like studying the original manuscripts in person.

Where are all the diaries kept?

The diaries, as private documents, remained in the hands of the Wilberforce family until relatively recently, though the largest single volume was acquired by the Wilberforce House Museum in Hull in the early twentieth century. The rest of the diaries (and religious journals) were only transferred to the Bodleian Library in Oxford in the 1980s. They were made available on microfilm, but they have been surprisingly little used.

Above - Wilberforce by John Rising (ca. 1790). Wilberforce House Museum Hull.

It sounds like an enormous undertaking, can you tell me a little about the reasons behind the project?

The project started from the recognition that Wilberforce’s unpublished manuscript diaries are a major text of the later Hanoverian age. They are obviously important for understanding abolitionism, but they will also be useful for the history of parliament, religion, domestic life, travel, reading and many other topics.

What do you hope to achieve?

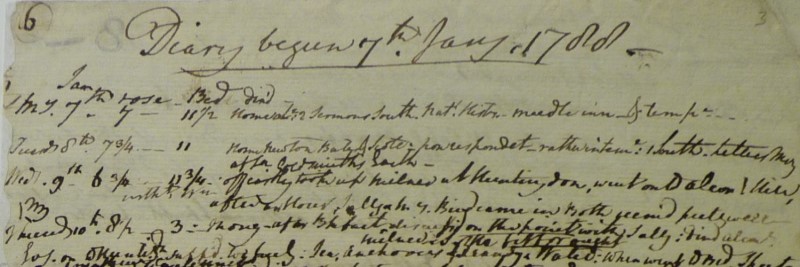

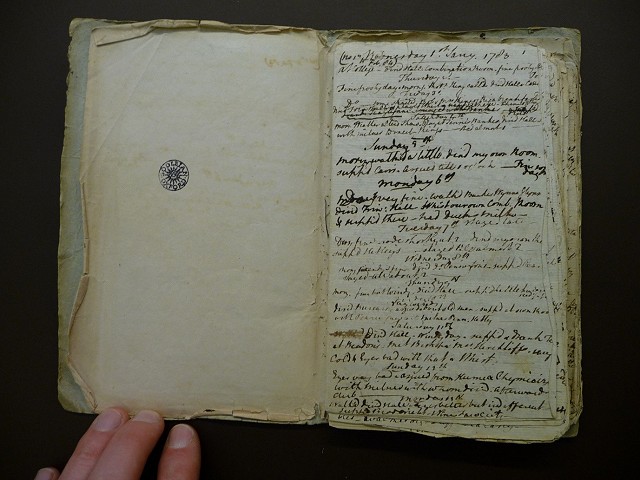

We aim to make an important piece of the historical record available for a new generation of readers and historians. Our first task has been to create a transcription of the manuscript diaries and journals. This is easier said than done, because Wilberforce’s handwriting in the diaries is almost illegible in places. Even at the best of times, it’s a slow read. Our second aim is to create a scholarly apparatus that explains what is going on in the diaries. Finally, we aim to disseminate our findings to a wider audience through a project website, Twitter account, publications and events.

How long do you think this will all take?

Projects of this scale typically require at least a decade to complete. We’ve been underway for five years and are now at the halfway point. We have a complete transcription of the diaries and journals (almost a million words) and are beginning to annotate the text. So we hope to submit to OUP in 2024 or 2025, with publication following 18 months later.

What processes are in place with transcribing and developing associated information?

We’ve now assembled a team of scholars to edit specific years. Besides ourselves at Leicester, the other editors are Dr Michael McMullen, Dr Mark Smith, Prof John Wolffe. We’ve also had valuable research assistance from several early career scholars. The current phase of the project involves editing and annotating the transcription, but also creating a catalogue of Wilberforce’s correspondence (currently over 2000 letters), a catalogue of his reading, and various appendices (e.g. of his itineraries).

What years do the diaries cover and are there any missing years?

Wilberforce kept diaries for over half a century, from 1779 (when he graduated from Cambridge) to 1833 (the year of his death and the Slavery Abolition Act). But the coverage is very uneven. For 1787 we have less than 1000 words, but for 1811 almost 50,000 words. Frustratingly, some of the diaries listed by Wilberforce’s son Robert are no longer extant. Robert had his father’s manuscript diaries for the years leading up to the abolition of the slave trade (1805-7), but we now have to rely on the extracts that were published in the sons’ 5-volume Life of William Wilberforce (1838). Yet the diaries do shed a flood of light on the neglected second half of Wilberforce’s career, from 1807 onwards.

Above - First page of the Wilberforce diary (1783 -86). Bodleian Library.

How frequently does Thomas Clarkson feature and what years?

There are almost one hundred references to Clarkson in the diaries, mainly clustered in the period between 1789 and 1791 and in the 1810s and early 1820s, when the two men collaborated closely. Although Clarkson is often numbered among ‘the Clapham Sect’, the diaries suggest an effective working relationship rather than an intimate friendship. Clarkson was never as close to Wilberforce – socially, religiously, or politically – as Henry Thornton or Isaac Milner or Thomas Gisborne. And personally, Wilberforce probably had a warmer friendship with John Clarkson than with Thomas. Yet the sons omitted their father’s praise for Thomas and included none of the 50 or so references to Clarkson in the diaries after 1790.

Their extracts concerning Clarkson came from 1789-90, but even here there are significant omissions: ‘How diligent Clarkson is: how they all shame me’; ‘how ought the diligence of Ramsay & Clarkson & Burgh to shame me’; ‘John Clarkson came to dinner – he slept on the Sofa – He shames me by his diligence & simplicity’. In 1790, when Wilberforce tells us that he ‘Look’d over Clarkson’s Witnesses’, the sons omit Clarkson’s name, obscuring his critical role in gathering witnesses against the slave trade. The diaries give a more honest account of Wilberforce’s relationship with Clarkson, noting tensions over Sierra Leone in the 1810s, as well as collaboration over European diplomacy and the King of Haiti, Henri Christophe. But one wonders what was in those missing diaries.

Is there anything that really stands out or perhaps tells us about the differences of the working relationships and approaches used by Wilberforce and Clarkson?

Clarkson and Wilberforce were constantly paired together, not least by American abolitionists, but they were very different figures. Physically, Clarkson was a bear of a man, whereas Boswell famously compared Wilberforce to a shrimp. Socially, Wilberforce inherited a fortune as the son of a wealthy merchant; Clarkson was the son of a parish clergyman and never affluent. Religiously, Clarkson was a latitudinarian Anglican with Quaker sympathies; Wilberforce was the leading Anglican Evangelical of his day. Politically, Clarkson favoured Charles James Fox and the opposition; Wilberforce was mostly aligned with the government of Pitt the Younger. And as abolitionists, there was a division of labour: Clarkson was the major orchestrator of popular abolitionism, whereas Wilberforce was a fixture of the Westminster establishment.

That said, one can exaggerate the gulf between them, as if Wilberforce was exclusively focused on the elite, Clarkson on the populace. Both had studied at St John’s College, Cambridge, albeit in different years, and they collaborated very closely between 1787 and 1792. They came together again in subsequent campaigns: the abolition of the slave trade in 1805-07, the attack on the French, Spanish and Portuguese slave trade in the mid-1810s, correspondence with Henri Christophe, king of Haiti, and the founding of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1823.

They were both extraordinarily good at mobilising others to work for abolition. Clarkson is rightly celebrated for creating the abolition society in 1787, instigating local committees, building national networks, recruiting witnesses, and liaising with French abolitionists, but he also lobbied statesmen and government officials. Wilberforce’s work was more focussed on Westminster, where he turned his inner circle into an engine of abolitionism and assiduously bent the ear of government ministers over many years; yet he too encouraged mass petitioning and sought to mobilise the British religious public against the Atlantic slave trade.

I have to ask, what’s the most unexpected entry you’ve found?

There are a lot to choose from: Wilberforce troubled by ‘lewd Ideas’ after flirting with a bishop’s daughter, or showing uncharacteristic fury at a critic of Sierra Leone (‘that vile demon Thorpe’), or recording the increasingly large doses of opium that he used for pain relief. We were surprised to find that Wilberforce had met Simon Bolivar, the South American ‘Liberator’. This was hiding in plain sight because the the diary entry (for 31 July 1810) appears in the official Life of Wilberforce: ‘Morning at Prayers…when in the Verandah appeard General Miranda & his 2 Caraccas Deputies, come to settle terms of friendly connection with this Country - countenance of one very peculiar - They staid till 12½’. Bolivar is not named, but research reveals that he was one of the 2 deputies from Caraccas. Annotating the diaries should reveal many more of these international connections.

And finally, about you both. It would be great to hear how this project relates to your previous research?

Coffey: In some respects, it is a marked departure from my previous research, because I worked intensively on religion, politics, and ideas in the English Revolution of the 1640s and 1650s. But thematically, the two periods have more in common than one might think, not least in the great importance of religion as a driver of reform (and a bulwark of reaction). Moreover, I got my taste for scholarly editing from working on an Oxford University Press edition of Richard Baxter’s Reliquiae Baxterianae (1696), one of the seventeenth-century’s major memoirs. It convinced me that scholarly editing was fascinating, enjoyable, and worthwhile. Major editions have a longer shelf-life than monographs, and they remain important reference works for decades to come. We hope that others will take up the challenge of editing Clarkson’s two abolitionist diaries (which are much shorter than Wilberforce’s), as well as his remarkable correspondence.

Harrington: My PhD thesis was a reassessment of Wilberforce’s abolitionist career, and I was lucky to be able to use early transcriptions of the diaries as part of my research. Working on the diaries now is very much a progression of the same, but I’m still finding more in the diaries that I missed previously! More broadly, the project means I get to explore aspects that I didn’t have the space or time to include in my thesis, from Wilberforce’s broader political career to potatoes.

And If people want to get involved in the project what do they need to do?

We can be contacted at wilberforcediaries@gmail.com, or on Twitter @DiariesProject.

This blog post is part of the ongoing Articles for Change project, funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund administered by the Museums Association.

The Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact. Since its launch in 2011, it has awarded 90 projects with grants totaling over £6.7m in 14 funding rounds. Between 2017 and 2019 it is offering a total of £3.5m in grants to Museums Association members, as well as providing events and resources for the whole sector. www.museumsassociation.org/collections

Share this article

Most recent news

Celebration for fans of Wisbech pubs book series

Celebration for fans of Wisbech pubs book series

Major civil engineering business backs Wisbech Museum with cash donation

Major civil engineering business backs Wisbech Museum with cash donation

Supporting the museum

To maintain and grow our collections we need your contributions, please support us by donating today.