Back to Blogs

Back to Blogs

26 July 2022

Reading Priscilla Peckover: Part 1. An Overlooked Pacifist Hero

The first in a 2-part blog series written by Museum Assistant, Riley Wade. The post of Museum Assistant is supported by the Government's Kickstart Scheme.

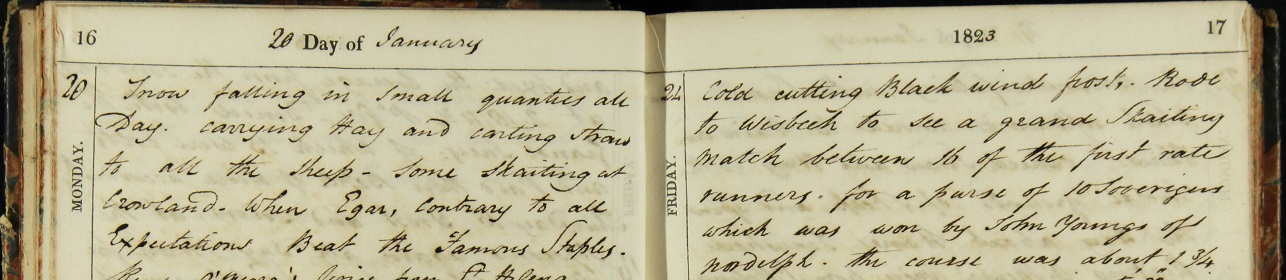

Priscilla Hannah Peckover was one of the most influential pacifist activists of the 19th century, and yet very few, even here in her hometown and base of operations, know about her. A Quaker, Peckover was born into the wealthy banking family of the same name and inherited from them a legacy of philanthropy and the pursuit of non-financial endeavours (a luxury afforded to her by her wealth and status). It was only during her forties that Peckover began to pursue an active role in the peace movement. Raised as she was by a Quaker family, notions of godly pacifism surrounded her from an early age. Notable around this time was the Peace Society (also known as the London Peace Society) which had been founded on Quaker beliefs by several significant pacifists, including John and Thomas Clarkson, also of Wisbech. While consisting nearly entirely of men, and reticent to pursue the burgeoning first-wave of feminism, it was first opened-up to women with the Women’s Peace Auxiliary or WPAAPS in the mid-1870s. By the early 1880s, Priscilla Peckover was an active member, and by 1882 was treasurer for the newly formed Ladies Peace Auxiliary after disagreements forced the WPAAPS to go independent. Ignited with a flame of passion, and with the authority to pursue her goals, Peckover soon rose through the hierarchy of the Peace Society- aiding the Ladies Peace Auxiliary while also setting about her most valuable contribution to pacifism: the founding of the Wisbech Local Peace Association (WLPA).

There is no denying the WLPA’s incredible impact on the status of pacifism both nationally and worldwide, and Priscilla Hannah Peckover’s leadership of it as fundamental to its rapid expansion. Her passion was consolidated in mass leafletting schemes, a penny per pamphlet, travelling all throughout the town spreading the simple word of peace through literature and speech. Hers, as the Peace Society’s, was an absolutist pacifism: one that denied the use of any violence, even as a means to combat violent institutions. This noble, if naïve, goal nevertheless helped garner a great deal of the association’s following. By 1880 it had more members than WPAAPS, by 1885 it accounted for over half the membership of all Local Peace Associations in the country, and by 1890 it consisted of 6000 people (more than 2/3 of Wisbech’s population at the time) with 80 distinct subbranches and members as far afield as New Zealand and Japan. The impact Peckover herself had on this was monumental, and soon she was somewhat of a celebrity among those who knew of her and her continuing efforts to motivate the populace into pacifist action. From speeches across the country, to the production of her own quarterly journal Peace and Goodwill: a Sequel to The Olive Leaf.

This passion, coupled with her closet-feminism made Priscilla Peckover a significant force in the peace movement. Some may condemn her conformity to systemic standards of womanhood, perhaps find it contradictory to the feminist ideals upon which WPAAPS and the Ladies Peace Association were founded, but as Heloise Brown notes ‘gave rise to more collaborative and conciliatory methods’ [Brown, 79], effectively utilizing her femininity toward political ends. Alongside this was a devotion to Christian beliefs and ethics which, again, despite outward appearances of concessions to power, actively aided in the struggle against war by helping to shape a strict morality and kindly flexibility that she was fiercely adherent to. While personally very private, perhaps even shy, her pamphlets and speeches show an underlying boldness which was unbound by national allegiance. In one (in)famous publication, Peckover released a transcription of an address by 2000 German women alongside Countess Butler-Haimhausen against British colonial violence, and the use of concentration camps in the Boer War, all this while no other publication (including major newspapers and pacifist pamphlets of the time) would. Objecting to the brutality of the British colonial war effort, Peckover herself wrote: ‘‘Have we been culpably blind as to what our officers and men were learning to do amongst semi-armed uncivilised [sic] races?’, and that ‘it is the truest form of patriotism to do our utmost to save our country from the crime and shame of an unjust war’. It is a profound statement, albeit one that is naïve to the exterminationist violence of the majority of colonial and imperial actions.

It was Peckover’s desire for pure human connection, violence instead replaced by communication and diplomacy, that led to her unique success in other endeavours, including the construction of the first full Esperanto Bible (the Londona Biblio) in 1926. What with Esperanto being a constructed language built for the intention of pan-european communication, it is understandable that Peckover would play a hand in its proliferation in the hopes that it could break down barriers between collective organizations of pacifists, and encourage civil, peaceful, communication more broadly. Peckover was extraordinarily dedicated to her peacekeeping aims, mediating all she did through them, even her skills as a talented linguist, Esperanto, more than a hobby, was another means by which the pacifism for which she had the utmost dedication could be transferred and exhibited, even in her old age.

This dedication, and her passion to deliver and preach the cause of peace at a time of seemingly unending violence (the Scramble for Africa, the after-effects of slavery abolition, the Boer Wars, WWI), and indeed her intentions to do so internationally with only her voice and diplomatic skills, are what got her nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize four times throughout her life. While Peckover never won the award, it is enough to know she was recognised in the field for her incredible talents, and global sensibilities. The profound impact that Peckover had on the international peace movement, especially as it pertained to women and expressions of femininity, was entirely deserving of such renown. While her skills in rhetoric and administration, and subdued nature may come across as less “exciting” than her more active boots-on-the-ground associates, they necessarily made for a figure whose apparent mundanities contributed genuinely and fully to a global desire for peace. The very foundation upon which organizations like the UN are built today. It is little wonder that in the society’s final address, the advice was to join the League of Nations Union, a group that would evolve into the modern United Nations.

And thus ends Part 1: where we find Priscilla Hannah Peckover in her very prime, a stalwart activist with an unshakeable demeanour and a community ethics even (and especially) in the swirling maelstrom of the early 20th century. In the second part we will discuss Peckover’s philosophy, flaws, and yet more of her enduring legacy, including what became of the WLPA.

Wisbech and Fenland Museum is currently hosting a display on the life of P. H. Peckover created by young volunteers participating in Changemakers, a National Lottery Heritage Fund project delivered by Museums in Cambridgeshire. Be sure to visit to learn more about Peckover, and our wonderful historic town!

Much of the research for this blog emerged from reading Heloise Brown’s book The Truest Form of Patriotism: Pacifist Feminism in Britain, 1870-1902. I highly recommend it for anyone seriously interested in the topics covered here.

Share this article

Most recent blog posts

Recent Accessions: Paintings from the collection of Ashley Whitteridge

Recent Accessions: Paintings from the collection of Ashley Whitteridge

A further view from the Chair.

A further view from the Chair.

A Tribute to Bill Knowles of Walpole

A Tribute to Bill Knowles of Walpole

Museum's Urnes Style Brooch recreated by Maria Holzleitner

Museum's Urnes Style Brooch recreated by Maria Holzleitner

Reading Priscilla Peckover: Part 2. On Accessibility, Violence, and the Power of Saying “No”

Reading Priscilla Peckover: Part 2. On Accessibility, Violence, and the Power of Saying “No”

Supporting the museum

To maintain and grow our collections we need your contributions, please support us by donating today.