Back to Blogs

Back to Blogs

14 September 2022

Reading Priscilla Peckover: Part 2. On Accessibility, Violence, and the Power of Saying “No”

The second in a 2-part blog series written by Museum Assistant, Riley Wade. The post of Museum Assistant is supported by the Government's Kickstart Scheme.

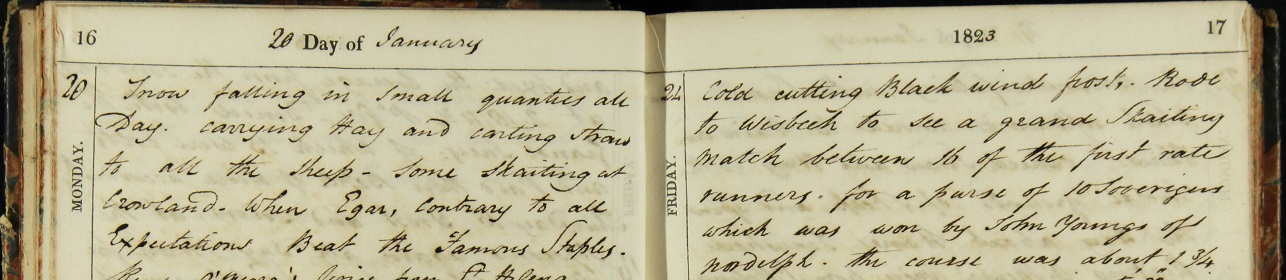

In Part One, we left Priscilla Hannah Peckover a sublime figure in the peace movement, remarkable in her skills as a public speaker, profound, but ultimately focused on small and significant changes to our pursuit of life and our tacit comfort with violence, and it is here that we follow. This was Peckover’s goal, the pursuit of the local rather than the national, lacking the perhaps hubristic naivety of the wider peace organizations, but making up for lost ambition in the form of strong ethics and workmanlike dedication. Hers was a pacifism of discussion, of the word, written or spoken, which could be distributed and talked over: pacifism as mediation, conversation, dialogue, diplomacy.

The symbol of Peckover, then, is one of habit – a character whose demeanour was not larger-than-life, profoundly calculated or radically incensed, but instead perfectly ordinary (albeit with visible wealth and status). This, along with her absolutist philosophy, lent itself to the notion that the pursuit of pacifism and nonviolence was and is totally accessible, a pursuit made possible through a simple act of denial, donation, and community participation, in effect losing the baggage of more radical forms of organization and community action toward pacifism, with the side-effect of losing those forms’ capacity for change. This was a pacifism of comfort, influence, and change tending toward the social and cultural rather than the political, not as protest but as ideological shift. It was this that was perhaps responsible for Peckover’s greatest successes: campaigning that targeted people’s better selves, that believed in the innate goodness of humanity, and facilitated that toward building a global peace movement. While much of Peckover’s naivety was due to her sheltered upbringing and ignorance toward material conditions of class, race, gender and ability (apparent in her privileged stance on feminism), her practical tendencies toward pacifist organizing were undoubtedly instrumental in promoting and celebrating the pacifist identity and the utopian idea of humanity’s perfect kindness. That kindness and innate goodness is a universalising ideology, one which opposed not good people from bad people, not pacifists from warmongers, but the entirety of humanity itself against the totality of war.

Representative of Peckover’s values is J. W. Butcher’s Condemned for No Crime, commissioned by Peckover herself and published on behalf of the WLPA’s printing fund in 1917. This short polemical autobiography is notable for its use of faith as the central motivator behind the politics (and they are politics) of pacifism, where in moments of fantastical delusion Butcher claims to be tempted by the Devil: the ‘god of War’. War here is a purely sinful act, in direct contrast to the holiness of conscientious objection and chosen passivity embodied by both the Peace Society and Quaker thought. Butcher’s actions are quite literally ‘No Crime’- his condemnation for the act of inaction and silence. It’s this that lies in direct contrast to anti-war movements over the years, including contemporaneously with the text. Where many movements such as emerging socialist and communist organizations, anti-imperialists, and feminists were involved in active struggle against the institutional status quo. Butcher’s and thus Peckover’s ideologies lent themselves to a kind of active passivity which became wholly accessible due to the simplistic nature of the practice- to be an objector all one needed to say was ‘no.’

It's this accessibility that led necessarily to the international spread of the WLPA, if participation in international peace-making needed only the intention to say ‘no’ when the time came, then anyone would be able to sign up and make a difference. In this process, more concerted efforts toward self-education could be made, as well as productive efforts of leafleting and conference attendance that were the passions of a young Priscilla Hannah Peckover, and which led to the foundation of the WLPA in the first place. The question is whether Peckover’s unerring absolutism led to much of anything, besides the transposition of pacifistic ideas. These ideas remained largely uncritical of the British establishment, as we can note from Butcher’s own depiction of the prison officers and military police guards, he notes that he tips them and that ‘I believe they both wished me well, and they hoped I should soon be out again’. It is a saintly position to present oneself in, wherein War and the military as symbols of violence are to be condemned, but not, for example, the corruptions of police and prison, both of which could justifiably be referred to as violent institutions. It is thus a fallacy to claim Peckover, or indeed the WLPA, absolutists when it came to peace, for the opposite of peace is not war, but violence.

Even so, Priscilla Hannah Peckover remains an unfairly forgotten symbol of local pacifist action whose outstanding leadership and eagerness to organise and educate remain high watermarks for activists today. Her subtle feminism and capacity to communicate beyond class barriers were necessary and profound steps toward an end which she undoubtedly believed in sincerely and fully, and thus which gained her enormous respect in our community. I am happy to say that that pride lives on, through our students, artists, historians, and community activists, whose remarkable strength and dedication, even in these less-repressive times, would surely live up to the Peckovers’ legacy.

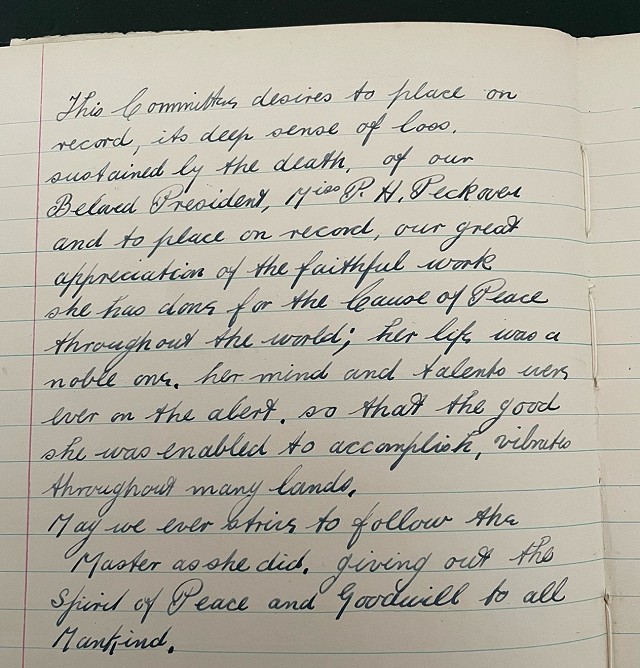

Priscilla Hannah Peckover died on 8th September 1931, at age 97, and presidency of the WLPA was succeeded by her niece, Alexandrina, whom she helped raise. An obituary, read on September 22nd of the same year reads as follows:

‘This Committee desires to place on record its deep sense of loss sustained by the death of our Beloved President, Miss P. H. Peckover and to place on record, our great appreciation of the faithful work she has done for the Cause of Peace throughout the world; her life was a noble one, her mind and talents were ever on the alert, so that the good she was enabled to accomplish vibrates through many lands.

May we ever strive to follow the Master as she did, giving out the spirit of Peace and Goodwill to all Mankind.’

On Monday 23rd July 1933, a decision was made to terminate the WLPA. But even now, its legacy, and the legacy of P. H. Peckover, lives on: with the urge to join the League of Nations Union, the gateway to worldwide pacifism wide open. That the Peckovers are so forgotten, Priscilla so forgotten even among them, in the discourse of modern pacifism is disappointing, but at least for now we can remember and reflect on the legacy of a truly remarkable woman. Maybe these blogs, this exhibition, these small interactions will raise interest. A fitting ode, I think.

Wisbech and Fenland Museum is currently hosting a display on the life of P. H. Peckover by students from Thomas Clarkson Academy. Be sure to visit to learn more about Peckover, and our wonderful historic town!

Supporting the museum

To maintain and grow our collections we need your contributions, please support us by donating today.