Back to Blogs

Back to Blogs

30 September 2019

Clarkson's Chest research

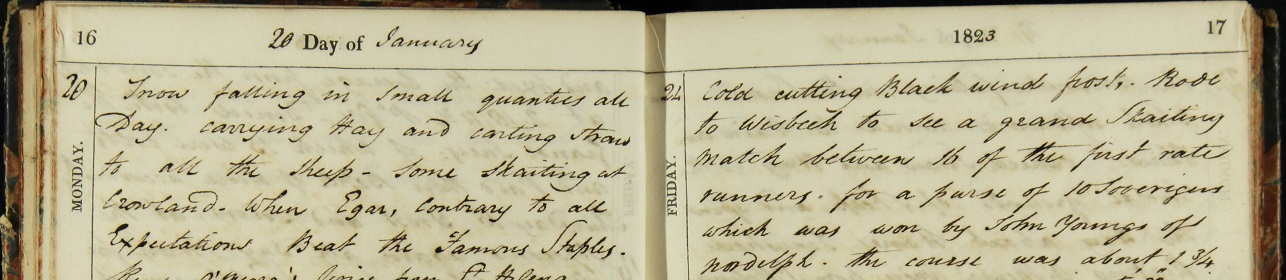

In my time completing work experience with the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, I was given an opportunity to observe the work of two researchers who came to investigate the textiles that are in Thomas Clarkson’s campaign chest. One of the main reasons for this research was that, well, no one has ever done it before.

Contemporary African textiles have been researched much more than older, as there are much less textiles still around from the West African coast before the 19th Century and specimens do not tend to survive. It is possible that the examples in Clarkson’s chest are some of the earliest available. Another purpose of the investigation is to determine where exactly the fabrics came from in West Africa. Clarkson never went to Africa himself, but purchased the textiles from merchants and slave traders in England. Of further interest are rare surviving examples of textiles using red thread. Before the 20th Century, vibrant red textile threads were very difficult to obtain with local dyes, but for many centuries West African weavers had access to cloth from elsewhere (in particular Europe and India) through the trans-Saharan trade and since the late 15th Century through the ships coming to the coast from Europe. Weavers would unravel these cloths to reuse the red thread in their own designs.

That being the case, Dr Margarita Gleba and Dr Malika Kraamer began their research. Dr Gleba specialises in archaeology of textile production in ancient times, whereas Dr Kraamer studies African textiles and fashion, especially the Ghanian kente cloth. Although their fields of research are different, by combining their knowledge they can accurately analyse the contents of the chest.

Dr Margarita Gleba and textiles from Clarkson’s Chest

The researchers kindly let me watch as they worked and explained the process to me. Destructive analysis was required for this investigation - Dr Gleba removed small samples of thread using tweezers. These samples are then sent off to a lab for different tests. They are viewed under an electron microscope which reveals the contents of the fabric. Then, the samples that are dyed can be analysed using liquid chromatography. Chromatography tells the researchers what the dyes are made of, which might help to pinpoint where they have originated as dyers in different parts of the world had different materials available to create dyes.

However, dye analysis is just one element to help to determine where these textile fragments originate from. Using a portable microscope, Dr Gleba was able to give already some initial thoughts on the type of fibres used and the direction the thread is spun. The magnified images show things like the width of the fibres and the direction in which the thread is spun, which indicate raw materials and what the production process was like. For example, historical African spinning produces a thread that has been spun clockwise, whereas an anti-clockwise thread is likely from Asia.

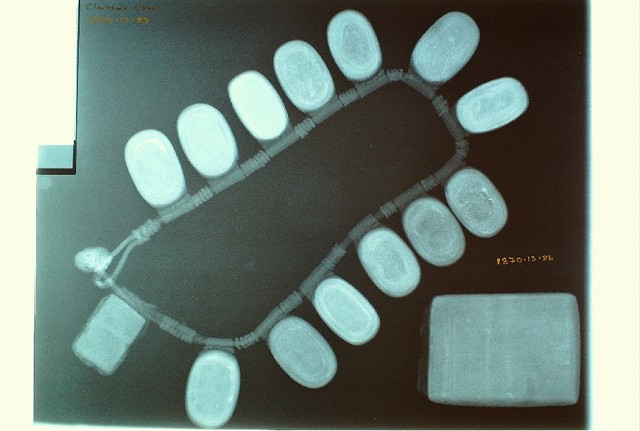

Leather beaded necklace from Clarkson’s Chest

During the process a discussion came up that really fascinated me. One of the artefacts in the Chest is a necklace with leather beads and an extra bead covered in fabric. The Museum’s Project Officer, Sarah Coleman, explained that the necklace had been x-rayed in a previous investigation and presented the x-rays to us. The x-rays showed that the leather beads are empty inside, but Dr Kraamer and Sarah Coleman suspected that the cloth bead had something in it. Dr Kraamer explained that it is common for many cultures, especially in the past, to place verses from the Quran inside necklaces like that as a form of protection (she also told me that it is best to avoid the word “talisman” as it has negative connotations). What was interesting is the fact that artefacts like that allow us to track the spread of religion. So, if we found a necklace that can be dated with a verse inside of it, it tells us that at a certain time this particular type of protection was used. Or, if there is nothing inside, it opens other questions. It could suggest that it was removed at a later date or it was prepared in a different way to give it protective attributions, or that it might be made purely to sell to Europeans and therefore there was no need to empower the object.

X-ray image

Speaking with Dr Gleba and Dr Kraamer, as well as watching them carry out their research, allowed me to find out about a whole new field of history that I have never thought about. It really isn’t often that you hear someone talk about West African handlooms from the 19th century! This was truly a unique and educational experience.

Dr Kraamer and Dr Gleba’s research forms part of the Articles for Change project funded by the Museums Association and the Esmee Fairbairn Collections Fund. The research is made possible through this funding and a grant from St John’s College, University of Cambridge.

For more information about this project please contact Sarah Coleman, Articles for Change Project Officer at Wisbech and Fenland Museum.

The Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact. Since its launch in 2011, it has awarded 90 projects with grants totaling over £6.7m in 14 funding rounds. Between 2017 and 2019 it is offering a total of £3.5m in grants to Museums Association members, as well as providing events and resources for the whole sector. www.museumsassociation.org/collections

Supporting the museum

To maintain and grow our collections we need your contributions, please support us by donating today.